FAQs – External Audits

Get the answers to your external audit, compliance and financial reporting questions.

What is a large proprietary company?

In 2019 the rules for what constitutes a large proprietary company changed, effectively doubling the criteria threshold.

As of 1 July 2019, a proprietary company is defined as ‘large’ for a financial year if it satisfies at least two of the following three criteria:

| Threshold | |

|---|---|

| Consolidated revenue of the company and any entities it controls | $50 million or more |

| Consolidated gross assets of the company and any entities it controls | $25 million or more |

| The company and any entities it control employs | 100 or more employees |

What are the reporting requirements for a large proprietary company?

Large proprietary companies are required to prepare and lodge a financial report and a director’s report for each financial year. The accounts must be audited by a registered company auditor unless an audit relief is granted by ASIC.

What is a small proprietary company?

If a company doesn’t meet at least two of the criteria to be considered a large proprietary company, it’s considered a small proprietary company instead.

In practical terms, a small proprietary company would be a business operating under a company structure with:

- At least one shareholder;

- No more than 50 non-employee shareholders;

- At least one director (who is an Australian resident); and

- A company secretary, if one is appointed.

What are the reporting requirements for a small proprietary company?

There are no standard requirements for a small proprietary company to lodge any form of financial reports or director’s reports to ASIC.

However, some circumstances may determine otherwise. For example, if the company is a wholly owned subsidiary of a company incorporated outside of Australia.

What is a disclosing entity?

As defined in section 111AC of the Corporations Act 2001 (Corporations Act), a disclosing entity is a corporation with enhanced disclosure requirements that the entity must adhere to.

For example, disclosing entities may be:

- Listed entities and listed registered schemes

- Entities and registered schemes which raise funds according to a prospectus

- Entities and registered schemes which offer securities other than debentures as consideration for an acquisition of shares in a target company under a takeover scheme.

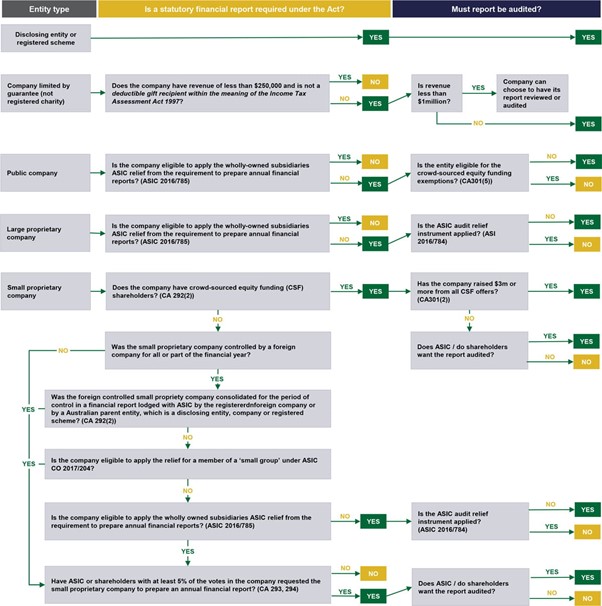

What is my company’s reporting and audit requirements?

What is considered a financial year for a company?

Under section 323D of the Corporations Act 2001 (Corporations Act), the first financial year for a company, registered scheme, or disclosing entity starts on the day it gets registered with ASIC. The first financial year typically lasts for 12 months, or—contrary to common logic—a period no longer than 18 months, as determined by the company’s directors (section 323D(1)).

Each following financial year must:

- start at the end of a previous financial year; and

- be exactly 12 months long.

Under what circumstances can a financial year be more or less than 12 months?

It sounds counterintuitive, but a financial year isn’t always a set 12-month period. While most companies operate under a full 12-month financial year, some entities may be allowed to operate under different rules.

| Exception | Requirements |

|---|---|

| A financial year that’s shorter or longer by seven days | A company can shorten or lengthen their financial year by up to seven days. This is to accommodate companies with week-based internal reporting. This can be done without seeking permission from ASIC —notification of the company’s intent to do so is acceptable. |

| A financial year that’s shorter than 12 months | A company is allowed to have a financial year that’s shorter than 12 months, as long as: • The previous five financial years have all been 12 months long; and • The change in length of the financial year is made in good faith, and is in the best interests of the company. As long as the company notifies ASIC of their intention to shorten the financial year, official permission isn’t necessary. |

| Synchronising with consolidated entities | If an entity has to prepare consolidated financial statements, then every company involved must do whatever is necessary to ensure all their financial years are synchronised. A company can shorten or lengthen their financial year to ensure this can occur. However, an extended financial year can’t exceed 18 months. Any entities that are required to prepare consolidated financial statements have the power to synchronise their financial years. However, this can only be done once, and must take place in the 12 months after the need to consolidate arises. The ability to change a financial year is available through the Corporations Act, which means the entities involved don’t need to seek permission from ASIC to change their financial years. Notification of their intention is all that’s required. |

| Synchronising with foreign parent | Similar to consolidated entities, a foreign-controlled company is allowed to lengthen its financial year so that it synchronises with its parent company. ASIC Corporations (Synchronisation of Financial Years) Instrument 2016/189 sets out the conditions for this to occur. However, onus is on the foreign controlled company itself to determine whether it can meet these conditions. If not, then it’s not advisable to synchronise its financial year. As above, approval from ASIC isn’t required. |

| Relief under section 340 of the Corporations Act | If a company doesn’t meet any of the other exceptions, then it can apply to ASIC under section 340 of the Corporations Act to change the length of its financial year. Generally speaking, the company must be able to clearly demonstrate that complying with a 12-month financial year would impose an unreasonable burden. Applications can be made through the ASIC Regulatory Portal, and must comply with requirements set out in the Corporations Act. For more information, refer to Regulatory Guide 43 Financial reports and audit relief (RG 43) and to Regulatory Guide 51 Applications for relief (RG 51). |

How do you define public accountability?

In simple terms, public accountability means that a publicly listed company is accountable to shareholders and other external parties who may be making economic decisions, but they aren’t able to request specific information or reports from the company.

As an example, a shareholder of a publicly listed company would probably not be able to request specific information or reports from the company and would have to rely on what the company publishes through ASX announcements.

On the other hand, a stakeholder of a local bowls club would likely be able to receive specific information from the club if requested.

An entity is considered publicly accountable if:

a) its debt or equity instruments are traded on a public market, or they’re in the process of issuing such instruments; or

b) it holds assets for a broad group of people in a fiduciary capacity, as part of its primary business.

Is my company publicly accountable?

Not every business is considered publicly accountable. The following for-profit entities have public accountability:

- disclosing entities, even if their debt or equity instruments aren’t traded in a public market;

- co-operatives that issue debentures;

- registered managed investment schemes;

- superannuation plans (as regulated by APRA); and

- authorised deposit-taking institutions, such as banks.

This means that, generally speaking, not-for-profit private sector companies aren’t publicly accountable.

What is a company limited by guarantee?

A company limited by guarantee is a public company registered under the Corporations Act 2001, that’s formed on the basis that, if the company winds up, its members’ liability is guaranteed to be limited to the amount that they individually contribute. This amount is set out in the company’s constitution.

It’s a company structure that’s typically used by not-for-profits and charities that reinvest their surplus profit back into the organisation.

In a company limited by guarantee, you’ll usually find that:

- It issues securities, rather than shares;

- It cannot pay dividends to its members;

- Directors have the same duties and liabilities as those in public companies—unless they’re registered as a charity with the Australian Charities and Not-for-profit Commission.

- A board of directors is required, which comprises three directors and a company secretary;

- Each member gets one vote.

What type of financial statements does my company need to prepare?

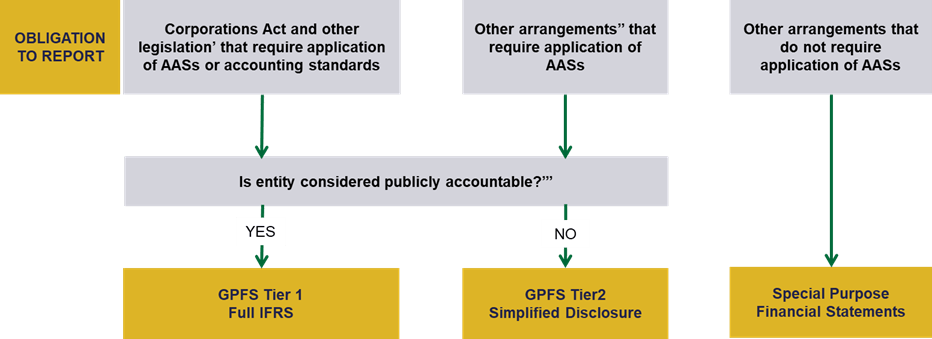

When it comes to financial reporting, the Australian Accounting Standards (AAS) consists of two tiers of reporting requirements which determine the general purpose financial statements (GPFS) that your business must prepare.

Your company will fall under one of these two tiers.

- Tier 1 Australian Accounting Standards. Tier 1 features requirements that are specific to Australian entities and incorporates full International Financial Reporting Standards. Entities that are publicly accountable typically fall under Tier 1 requirements.

- Tier 2 Australian Accounting Standards – Simplified Disclosures. Tier 2 includes the recognition and measurement requirements of Tier 1, but with substantially reduced disclosure agreements. These are set out in AASB 1060 General Purpose Financial Statements – Simplified Disclosures for For-Profit and Not-For-Profit Tier 2 Entities. An entity that isn’t publicly accountable has the option to use either Tier 1 or Tier 2 reporting requirements.

The diagram below shows how the Tiers work in relation to financial reporting for for-profit private sector entities under the revised Australian Accounting Standards.

‘ Includes Commonwealth, State and Territory legislation

” When preparing financial reports according to Australian Accounting Standards by other than legislation (e.g., constitution, trust deed), only if document is created or amended (for any reason) on or after 1 July 2021. Those created before 1 July 2021 are grandfathered to be permitted to prepare special purpose financial statements

What are the reporting timelines for companies reporting to ASIC?

Different types of companies have different ASIC reporting timelines. It can be quite convoluted, so we’ve aimed to break them down clearly and simply in this table.

| Type of company | When to lodge an Annual Report with ASIC |

|---|---|

| DISCLOSING ENTITIES | |

| Listed company | Within 3 months following the end of the financial year. Note that ASX is an agent for ASIC, which means that lodgement with ASX represents lodgement with ASIC. |

| Listed registered scheme | Same as a listed company. |

| Unlisted public company | Within 3 months following the end of the financial year. |

| Unlisted registered scheme | Within 3 months following the end of the financial year. |

| NON-DISCLOSING ENTITIES | |

| Registered scheme | Within 3 months following the end of the financial year. |

| Unlisted public (excluding small companies limited by guarantee) | Within 4 months following the end of the financial year. |

| Small company limited by guarantee (under ASIC direction or 5% of member direction) | No lodgement is required, subject direction by ASIC. |

| Large proprietary company | Within 4 months after the end of the financial year |

| Small proprietary company – foreign controlled | Within 4 months following the end of the financial year. |

| Small proprietary company – ASIC direction | ASIC will direct when to lodge the Annual Report. |

| Small proprietary company – 5% shareholders’ direction | Only required to issue annual report to the members within 2 months after date of direction, no later than 4 months after the end of the financial year |

What are the financial requirements of an Australian Financial Services License (AFS Licence)

In order to fulfil its licence obligations, a financial services business must adhere the obligations set out in Section 912A of the Corporations Act 2001.

ASIC have created a guide to support these requirements, Regulatory Guide 166: Licensing: Financial requirements, which was updated in July 2022. This guide helps users understand the requirements of their financial licence, and their obligations under this licence.

A brief summary

There’s a lot contained within the guide. But in summary, there are three base level financial requirements that financial services businesses must meet.

These are:

- Solvency and positive net assets. At all times, the licence holder must be solvent and have total assets that exceed their total liabilities. Essentially, they must be able to pay their debts.

- Cash needs requirements

The licence holder must have sufficient resources to meet any anticipated cash flow expenses. - Audit requirements

The licence holder must ensure that their audit report includes information demonstrating their compliance with the financial requirements.

Additional financial requirements

The Regulatory Guide includes a table that summarises the financial requirements for all categories of licence holders. It explains the base level requirements in more detail and include additional requirements that licence holders may need to be aware of (such as net tangible assets, surplus liquid funds, and other adjusted surplus funds requirements).

These additional requirements require individual calculations that the licence holders need to make, which should be monitored regularly, in order to meet the licence holder’s policy.

We want to make sure that all of our clients understand the financial requirement obligations you’re subject to as an AFS licence holder. Click here for a table that summarises the requirements based on your category of licence.

What is the difference between a charity and a not-for-profit entity?

A charity is a not-for-profit organisation—but being a not-for-profit doesn’t make an organisation a charity. So, what’s the difference?

A charity:

- Is a not-for-profit entity where all charitable donations must be used for public benefit.

- May perform secondary work that isn’t charitable in itself, but goes towards supporting the business’ charitable purposes.

- Is governed by the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission Act 2012.

A not-for-profit organisation: - Provides services to support a community but doesn’t operate for profit or personal gain of its members.

- Does not distribute profits to owners or members. All profits that it makes are invested back into its services.

- Is governed by the incorporated association act of its state or territory—unless the organisation is incorporated as a company.

Charity size and reporting requirements

We’ve summarised the reporting requirements for charities registered with the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission (ACNC).

| Small | Medium | Large | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annual revenue threshold | Under $500,000 | $500,000 – $3 million | $3 million or more |

| Annual information statement required to be lodged with ACNC | YES | YES | YES |

| Annual financial report to be prepared | Optional | YES | YES |

| Basis of accounting | Cash or Accrual | Accrual | Accrual |

| Audit or review | No obligation for either review or audit | Either review or audit | Audit required |

For more information, you can find a more in-depth explanation of each requirement on their website.

Not for profit size and reporting requirements

The reporting requirements for not-for-profit organisations, which aren’t registered charities, differ from state to state. We’ve summarised them in the following tables.

Western Australia follows the Associations Incorporation Act 2015.

| Tier | Classification threshold | Annual financial report required | Audit or review |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tier 1 | Revenue less than $500,000 | Yes, either cash or accrual | Not required |

| Tier 2 | Revenue of $500,000 – $3 million | Yes, in accordance with accounting standards | Review or audit |

| Tier 3 | Revenue exceeding $3 million | Yes, in accordance with accounting standards | Audit |

New South Wales follows the Associations Incorporation 2009.

| Tier | Classification threshold | Annual financial report required | Audit or review |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tier 1 | Exceeds either: gross receipts of $250,000; OR Current assets of $500,000 | Yes, in accordance with accounting standards | Audit |

| Tier 2 | Does not meet Tier 2 threshold | Yes | Audit required at discretion of Secretary |

Victoria follows the Associations Incorporation Reform Act 2012.

| Tier | Classification threshold | Annual financial report required | Audit or review |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tier 1 | Revenue less than $250,000 | Yes, in accordance with accounting standards | Review |

| Tier 2 | Revenue of $250,000 – $1 million | Yes, in accordance with accounting standards | Review |

| Tier 3 | Revenue exceeding $1 million | Yes, in accordance with accounting standards | Audit |

Queensland follows the Associations Incorporation Act 1981.

| Size | Classification threshold | Annual financial report required | Audit or review |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small | Revenue less than $20,000 | Yes, either cash or accrual | Audit if required by another law |

| Medium | Revenue of $20,000 – $100,000 | Yes, either cash or accrual | Audit if required by another law |

| Large | Revenue exceeding $100,000 | Yes, either cash or accrual | Audit |

Northern Territory follows the Associations Act 2003.

| Tier | Classification threshold | Annual financial report required | Audit or review |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tier 1 | Annual gross receipts under $25,000; and Gross assets under $50,000 | Yes, in accordance with accounting standards | Audit |

| Tier 2 | Annual gross receipts $25,000 – $250,000; and Gross assets $50,000 – $500,000 | Yes, in accordance with accounting standards | Audit |

| Tier 3 | Annual gross receipts over $250,000; and Gross assets over $500,000 | Yes, in accordance with accounting standards | Audit |

South Australia follows the Associations Incorporation Act 1985.

| Tier | Classification threshold | Annual financial report required | Audit or review |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prescribed associations | Gross receipts over $500,000 | Yes, in accordance with accounting standards | Audit |

Australian Capital Territory follows the Associations Incorporation Act 1991.

| Size | Classification threshold | Annual financial report required | Audit or review |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small | Total revenue less than $400,000 | Yes, in accordance with accounting standards | Review |

| Medium | Total revenue of $400,000 – $1 million | Yes, in accordance with accounting standards | Audit |

| Large | Total revenue exceeding $1 million | Yes, in accordance with accounting standards | Audit |

Tasmania follows the Associations Incorporation Act 1964.

| Classification threshold | Annual financial report required | Audit or review |

|---|---|---|

| Small | Yes, in accordance with accounting standards | Not required |

| Medium | Yes, in accordance with accounting standards | Audit |

What is the difference between private and public ancillary funds?

Ancillary funds provide the important link between donors and organisations that receive their donations. There are two types of ancillary funds:

- Private ancillary funds. These are charitable trusts set up privately by organisations, families, or individuals, that provide an investment structure for their philanthropy.

- Public ancillary funds. These are the typical organisations we think of as charities, which are set up to fundraise and receive charitable donations from the broader public.

There are some major differences between private and public ancillary funds:

| Private Ancillary Fund | Public Ancillary Fund | |

|---|---|---|

| Donations | Can’t seek or accept donations from the general public. | Collects donations from the general public. |

| Legislation | Taxation Administration (Private Ancillary Fund) Guidelines 2019. | Taxation Administration (Public Ancillary Fund) Guidelines 2022 |

| Minimum number of responsible persons | Must have at least one responsible person | The majority of people involved in the fund’s decision making must be responsible persons. |

| Minimum annual distribution rate | At least 5 percent of the market value of its net assets (at the end of the previous financial year). | At least 4 percent of the market value of its net assets (at the end of the previous financial year). |

| Audit requirement | An audit is required if the fund meets either of the following conditions: a) Revenue of less than $1 million; or b) Assets of less than $1 million. | An audit is required if the fund meets either the following conditions: a) Revenue of less than $1 million; or b) Assets of less than $1 million. |

What are variable outgoings?

Variable outgoings can mean different things in different contexts. In this context, we’re addressing variable outgoings in relation to each state or territory’s Tenancy Act.

Generally found in retail and commercial real estate, variable outgoings are sometimes also referred to as outgoings, or operating expense outgoings.

In its simplest form, a variable outgoing is an operating expense for the property that the tenant is required to pay.

When a commercial, retail, or industrial tenant takes hold of a lease, their lease agreement will include costs payable by the tenant, in addition to rent, that covers a proportion of the landlord’s operating expenses. These operating expenses typically cover any general or common area costs incurred in operating, repairing, or maintaining the property, such as:

- cleaning costs;

- air conditioning;

- security;

- insurances;

- rates; or

- taxes.

For retail tenants, your state might have specific legislation that imposes certain provisions about what can and cannot be recovered by the landlord—so check with your relevant state or territory legislation.

Variable outgoings usually aren’t something that residential tenants need to worry about.

What are the different types of leases?

While state and territory has its own Tenancy Act, they all follow similar definitions of the different types of leases within commercial and retail real estate.

These are:

| Type of lease | Definition |

|---|---|

| Net lease | The lessee contributes towards rental payments plus a relevant portion of the outgoings. This portion is calculated as the tenant’s lettable area divided by the property’s total lettable area. |

| Gross lease | The lessee contributes a fixed rate per square meter and no additional amount is contributed for outgoings (All-inclusive rent). |

| Semi-gross lease | The tenant contributes rent and limited operating expenses, which covers things like land tax, local government rates and taxes, water rates, and taxes. |

| Speciality lease | Determined on a case-by-case basis, these sees certain tenants have special clauses regarding outgoings. For example, some expenses may be capped, or only external maintenance repairs are charged. |

What are the reporting requirements in respect of outgoing expense statements for retail shops?

Interestingly, the commercial real estate reporting requirements for every state and territory in Australia are remarkable similar. The only exception is Tasmania, which differs slightly.

Under each applicable piece of legislation, the reporting requirements are:

- The reporting period is within 3 months following the end of the accounting period; and

- An audit is required, subject to exemptions.

In Tasmania, reporting requirement and audit requirements are only relevant if they’re requested by the tenant.

The exemptions to each state’s legislation are also similar, and in fact, some may be exactly the same from state to state. However, there can be nuance in their wording, so it’s important to read the relevant exemptions for your state carefully.

| State or Territory | Applicable legislation | Relevant exemptions |

|---|---|---|

| ACT | Leases (Commercial and Retail) Act 2001 | If the outgoings relate to water, sewerage & drainage rates, insurances, other rates and statutory charges, and specific contributions under the Unit Titles (Management) Act 2011, the report doesn’t need to be prepared by an auditor, nor contain an auditor’s statement. |

| NSW | Retail Leases Act 1994 | If the outgoings relate to water, sewerage & drainage rates, land tax, local council rates and charges, insurances, or strata levies, and copies of all assessments, invoices, and proof of payment can be supplied, then an auditor’s report isn’t required for the outgoings statement. |

| NT | Business Tenancies (Fair Dealings) Act 2003 | If the outgoings only cover charges other than water, sewerage & drainage rates, council rates and charges, and insurances, and copies of all assessments, invoices, and proof of payment are supplied along with the landlord’s statement, then an auditor’s report can be avoided. In the instance of multiple tenants, and each tenant can supply the relevant information that relates to them, then the outgoings statement can be a composite statement. |

| QLD | Retail Shop Leases Act 1994 | In the instance of multiple tenants, and each tenant can supply the relevant information that relates to them, then the outgoings statement can be a composite statement. |

| SA | Retail and Commercial Leases Act 1995 | If the outgoings only cover charges other than the emergency services levy, water & sewerage charges, local government rates and charges, and insurances, and copies of receipts for all expenditure are supplied, then an auditor’s report isn’t required. In the instance of multiple tenants, and each tenant can supply the relevant information that relates to them, then the outgoings statement can be a composite statement. |

| TAS | Fair Trading (Code of Practice for Retail Tenancies) Regulations 1998 | A tenant can request their landlord provide an audited report of their outgoings for any accounting year (either as set out in their lease, or if not, the general financial year). When requested, the landlord must provide this report within three months of the end of the current accounting year. If an auditor finds the landlord’s statement to be at least 95% accurate, then the tenant is required to pay the audit costs. |

| VIC | Retail Leases Act 2003 | If the outgoings don’t cover any charges other than GST, water, sewerage & drainage charges, municipal council rates and charges, insurance, fire services property levy, and owners corporation fees, and copies of all assessments, invoices, and proof of payment are supplied, then the outgoings statement isn’t required to be audited. |

| WA | Commercial Tenancy (Retails Shops) Agreement Act 1985 | If the outgoings statement only covers land tax, water, sewerage & drainage charges, local government charges, or insurance premiums, and copies of all assessments, invoices, receipts, or other proof of payment are supplied, then an auditor’s report isn’t required. In the instance of multiple tenants, and each tenant can supply the relevant information that relates to them, then the outgoings statement can be a composite statement. |

Get started today

Contact our team today to book a free consultation and discuss

how our expert auditing services can enable better business.